Where woud we be without lugworms? We take them for granted, moan like hell when the tackle shop hasn’t got any and probably waste more than we use. Steve Walker looks into their lifestyle and explains how to collect and care for black lugworms.

Sea anglers have known for years that not all lugworms look alike, that they inhabit different types of ground and that there are surely more than one species.

Swansea University researchers uncovered the fact that black lug is a different species to blow lug, and having attended a lecture at the Dove Marine Laboratory at Tyneside I found out there at least two more types of lug living around our shoreline.

You know what lugworms look like but did you know the thicker thoracic part of the body has bristles (chaetae), the last 13 segments of which also have feathery gills, and the much thinner tail end or abdominal part has no bristles or gills.

Actual genetic differences between blows and blacks may be difficult to spot, but anglers can usually tell them apart by their different colour, size and the different type of casts they make.

Black lug can grow to 40cm or more and, as their name suggests, they are a dark colour, varying from an almost black, very dark green, to a more recognisable mid-green, to a dark brown.

The cast is usually a neat coil resembling a rolled up hosepipe, but sometimes it is just a small blob that is difficult to see. Black lug are often found at the lowest reaches of a low tide and can burrow to considerable depths.

When handled they will leave a yellow stain on the fingers. They are not as common as blow lug and are difficult to dig because they are only usually available on bigger low tides.

Blow lug are much smaller, rarely exceeding 20cm, their casts are often a large squiggly mess, accompanied by a round depression in the sand created while feeding in their u-shaped burrow.

Black lug casts don’t have this depression because they live much deeper in a j-shaped burrow possibly using a different feeding method.

Blow lug are more likely to be found on the upper and middle reaches of a beach and are more likely to be a pink, reddish-yellow colour, although in some places blow lug actually look black.

They are generally easy to dig because they inhabit most of the beach and don’t burrow very deep. Large colonies of immature blow lug congregate in nursery areas usually at the top of a beach, but immature black lug have never knowingly been found and it may be that they live below the low tide mark.

To confuse matters lugworms are also known as yellowtail or browntail, which also leave a yellow stain on the fingers. This has a cast somewhere between the blow and black lug, which is often not quite as neat as the black lug, but also not quite as messy as the blow lug. This worm tends to live in the middle regions of a beach and may be an almost mature black lug or a different species.

This is just interesting biology because whatever worms you either dig or buy will catch fish, so I am just going to stick to calling them black and blow lug.

Blow lug are normally available from tackle shops because they are more readily available and easier to dig. Black lug, or runnidown as they are known in the North East, are more difficult to get, and are usually only available from tackle shops by special order; don’t be surprised to pay £5 or more for ten.

Left: You can use either a bait pump or trenching spade to dig black lugworms.

Right: Pumping is more effective when the ground is wet.

Digging for victory – your simple guide to how it’s done…

Digging your own bait is relatively easy once you have found the worm beds, but it depends on the ground they inhabit. Black lug are usually dug on big spring low tides and are usually lifted one at a time, although occasionally you may be able to trench two or three out of a single hole before moving to find another cast.

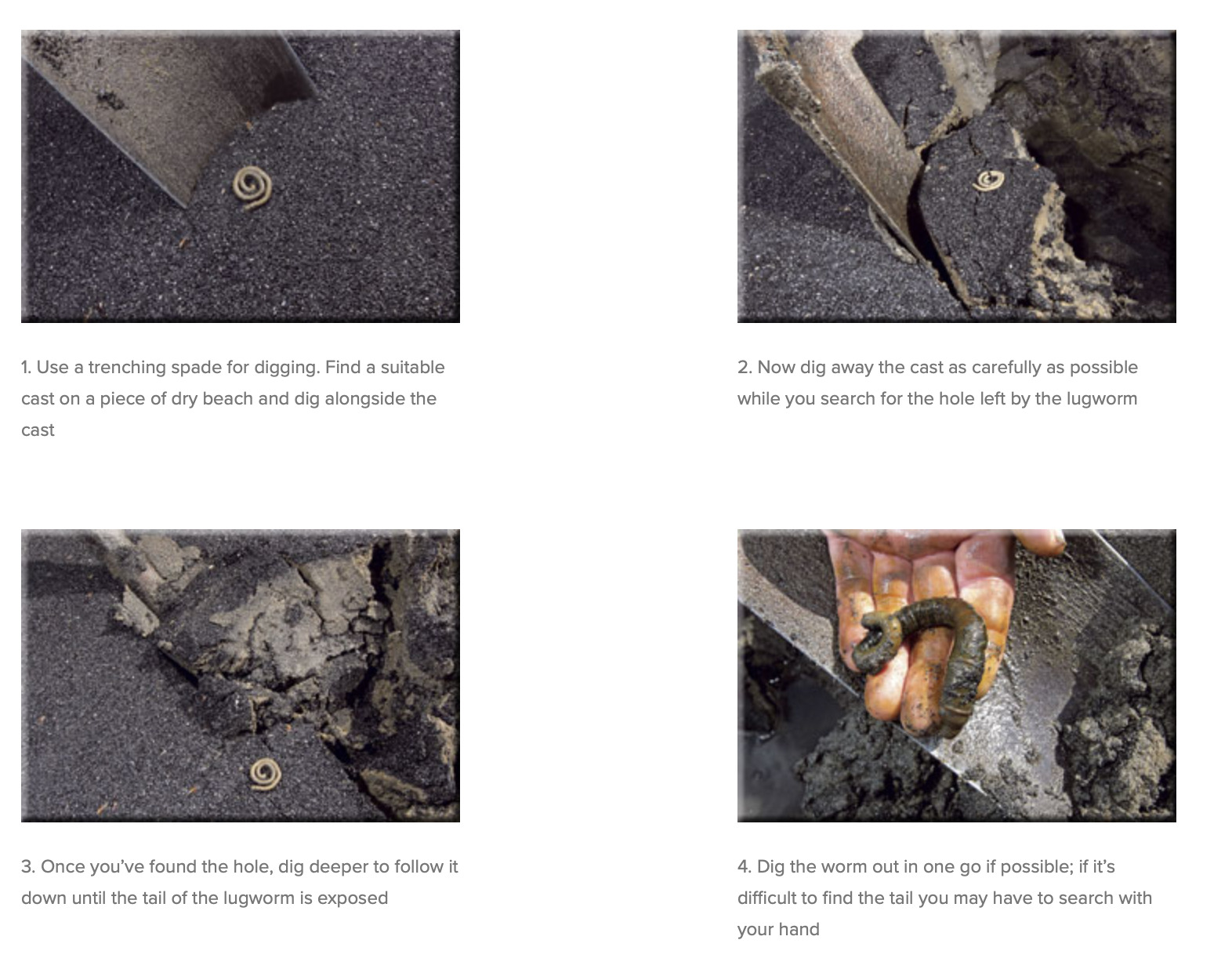

Because of the depth at which they go to, a trenching spade or spit is a better tool to use than a fork. Find a suitable cast on a bit of dry beach and then dig alongside the cast.

Carefully dig away the cast to reveal the hole left by the worm and then dig down deeply again in the first hole to repeat the process and follow the wormhole down until the tail is exposed.

When you get to this stage, dig the worm out in one go if possible. If it is difficult to find the tail section, then you will have to thrust your hand down into the wet sand, grab hold of the tail, then carefully work it free.

If the sand is heavily rippled and holding water then you will need to dig a drainage hole somewhere away from the cast to drain surface water away from where you want to dig. If the beach is heavily waterlogged and the worms are deep, then digging could be difficult and the rewards few.

You could use a bait pump to extract worms from a roughly straight burrow, but it takes a bit of practice to get it right. Anglers pumping for the first time make the mistake of pumping down to the worm and, as a result, cut it in half. You should keep the pump just a few inches below the surrounding surface and suck the worm upwards. Pumping tends to be more effective when the ground is wet because this improves suction. Sometimes it is necessary to pour more water down the hole to increase suction.

Now your freshly dug lugworms need some intensive care…

Whether they are dug or pumped a lot of worms will blow their guts when exposed and they need a lot of attention to keep them in good condition.

You will need two buckets to do the job properly; a larger main bucket and a smaller one that fits inside to hold the damaged worms.

Blown worms can either be used immediately, just wrap them up in newspaper ready for fishing or freeze them for later use.

For freezing I give the worms a quick wash in fresh sea water then dry them out for a few minutes on some thick absorbent paper towels. I then wrap them up in tissue paper, which soaks up any remaining body fluids and place them on a metal tray in the freezer until they have frozen properly.

Finally wrap them up five at a time in cling film and place four parcels of five worms into a sealed sandwich bag. A group of five is just about right to store in a wide mouthed flask to take fishing and I can usually manage to get around four parcels of them into a single flask.

I keep worms in shallow trays in a fridge, taking care not to overcrowd them. I change the water once a day, just a few millimetres is all that’s needed, and keep a careful watch on them, removing and freezing any that look a bit worse for wear.

If a worm bursts and you get to it too late all of the other worms will quickly do the same, which is why some anglers prefer to gut the worms prior to freezing by squeezing out all of the body contents. When defrosted they look like a tough stick of liquorice. I prefer to keep all of the guts in because it holds all the scent.

The best places to dig are often those most sheltered from a prevailing wind and sea, such as an estuary.